I wanted to use this post as an opportunity to share about one of my most challenging rounds of Reading Recovery. All four of my students entered with mostly stanines of 1 for each task on the Observation Survey and very low raw scores. My students required various types of support to help with significant speech and language delays, large motor and fine motor delays, poor attendance, and struggles with disruptive behavior in kindergarten that led to a lot of missed instruction.

As Reading Recovery teachers are trained to do, I entered this round thinking very positively. I was ready to roam and around the known and set the stage for discovery. As my students and I entered into our first lessons, I still remained optimistic and was excited by my students’ reading and writing behaviors and their own excitement about each reading and writing task. After a couple of weeks of lessons, I started to feel the stress of supporting each of their unique needs. I was needing to dig into Literacy Lessons Designed for Individuals (LLDI) (2016) and search for other resources on supporting oral language, letter formation, motivation, and difficulties with remembering. I found myself constantly thinking about each one of my students and how I was going to meet their needs. I was even dreaming about doing the lessons I had written that day and envisioning their outcomes!

Now the first round is coming to an end. One of my students demonstrated accelerated progress and will no longer be receiving reading intervention services, but will be monitored. Two of the other students who did not show accelerated progress or even a progressed designation have still shown a full year’s worth of growth in 20 weeks. I have learned so much from all of my students this year, but for the remainder of this post I want to reflect on the student that puzzled me the most.

This particular student’s raw scores were quite similar to my other Reading Recovery students with the expectation of letter ID, which was quite a bit lower (12 letters – 6 uppercase and the same 6 lowercase). He knew 5/24 concepts about print and could not read any words, could not write any sounds that he heard (he wrote a few numbers and drew 2 stars), was able to write 1 word – his name, and was able to read back the dictated sentence that we had created together. I wasn’t overly concerned because I knew he had missed a lot of school during kindergarten. We would just start working with what he knew and go from there. During the administration of the Observation Survey, my student was very animated and excited to share with me how much he loves books. He initially approached each task confidently and then would be apologetic as he struggled with the task.

During roaming around the known, he easily picked up basic concepts about print, held on to the patterned language of the books we were reading, quickly picked up on pointing word by word with my modeling, found known letters, found his name, he demonstrated beautiful letter formation, demonstrated strong oral language, became fast and fluent with his known letters, and showed excitement for reading and loved to create his own stories, especially stories involving lizards.

As we moved into the first few weeks of lessons, I started to teach new letters and some words. We did daily letter sorts with magnetic letters, made the letter he was learning numerous times using the verbal path with many different types of materials, found the new letter in his books, used an ABC book that we created for the letters he knew. Over time, I noticed that he wasn’t holding on to the letters or words that I was teaching. It was very challenging for him to remember letter/word learning from moment to moment and place to place during the lesson and across days. Throughout this period, I discussed the problem with my colleagues and tried some suggestions, but progress was still minimal.

I felt an urgency to help my student learn more than the 12 letters he knew upon entering Reading Recovery. Marie Clay tells us that “children who know only a few letters will learn words very slowly” and this was exactly what I was seeing with my student. Clay also writes that while we should “respect the child’s pace of learning” we still need to “get the entire set of letters known as soon as possible (LLDI, p. 62).” I needed to figure out how to make my student’s letter learning experiences more memorable.

What made the shift needed in my teaching was on-going support from my teacher leader. My teacher leader asked just the right questions to get me thinking about my decisions, watched my teaching carefully to see if I was doing anything that might cause confusion, watched my student closely to notice behaviors that I might be missing, and guided me to the most helpful sections in LLDI.

In case you are curious, I will share some of the things that helped to make a shift in this student’s learning. Keep in mind that these are the things that worked for this particular student and may not work for all students struggling to learn letters.

I became even more intentional with my teaching of letters. I carefully chose letters that I noticed he knew something about or that caught his eye. At times, I gave him some control over the letter that he wanted to learn next. For example, he enjoyed the part in The Farm Concert by Joy Cowley when the farmer yelled, “Quiet!” That “Q” caught his eye and he asked me if he could learn that letter next. I documented any letter learning activities that we did together and his reaction to it. I thought outside of the box about what activities this particular child would enjoy. I kept careful documentation about how long it took to learn a letter.

Once I could see better which letter learning activities were catching his attention, I stuck to that menu of options for several letters. At that time, it was taking him just over a week to learn a letter. After that, the next couple of letters took 4-5 days to learn. For the first time, when he knew about 21 letters, he started to learn letters that he wasn’t explicitly taught.

Here are a few of his favorite letter learning activities:

- Making the letter in shaving cream (every time we used shaving cream he would say, “this is such a satisfying feeling!”)

- Singing a letter song (he LOVED the Jack Hartman letter songs)

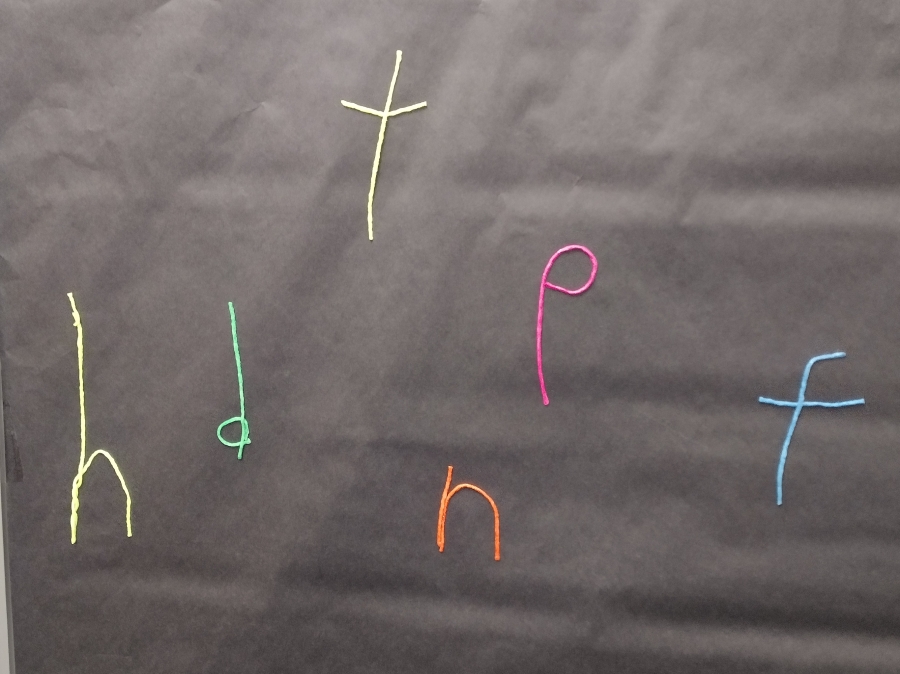

- Making the letter out of wiki stix (once he knew the letter he decorated the wall with the wiki stix letter he had made)

- He made up his own verbal path for each letter (some came from what he learned in the classroom, ex. “ball, then bat” made the letter d)

- Reading an alphabet tracing book “Jan Richardson-style” (I went over the letters with puffy pant to give them a textured feeling)

- Reading the Rosie and Bella letter books

- I met him at his classroom with an item that started with the letter he was working on. For example, I brought a stuffed fox when we were working on the letter f because I knew he loved animals (he enjoyed the surprise and would even try to guess the day before what I might bring next time)

While doing all this thinking and planning about letter learning, I reminded myself that the letter and word learning in isolation should be a small part of the lesson. I could still continue working on letter learning within the context of reading and writing by explicitly connecting his familiar letters and the new letter he was learning with the text. I noticed that being very intentional with book choices helped in making memorable connections. Helping my student recognize what he knew embedded in text, led to my student noticing and pointing out things he knew in the environmental print he was seeing in school and his mom was noticing it happening at home too!

At the end of the lesson series, this student did not show accelerated growth or fall in the progressed category, but his time in Reading Recovery was valuable because it helped to identify what teaching moves supported this child with learning. Much of the teaching that was done in Reading Recovery could be applied to other areas in his day, such as learning numbers during math.

I would currently describe my student as a strategic, confident, happy reader (when reading at his instructional level). He is proud when he monitors and self-corrects his reading. During our last week of lessons, he beamed from ear to ear when he did a letter by letter sound analysis, when reading an unknown word, all on his own with no prompting or support. He excitedly reread the sentence as if shocked that he actually figured it out.

Although reading and writing has been a challenge for this student, he continues to share with others that he loves to read. He clearly sees himself as a learner as he makes comments about how he “fixed” his reading or how he figured out a word and says, “I’m smart!” when he makes a new accomplishment.

I think at this point in time, Reading Recovery teachers feel a lot of pressure to prove that Reading Recovery works. Of course, I wish I was able to get things going faster for my student. I wish he ended his lesson series reading on-grade and that things would become easier for him. At the same time, I think Reading Recovery was vital to the success and growth this student was able to experience at the beginning of his first grade year. I took the stance that it was up to me to figure out how to teach this student. It wouldn’t be productive to sit back and blame the child for his lack of progress. Reading Recovery helped this student stay motivated and feel successful even when he had little item knowledge because I always worked with the student where he was at not where I wanted him to be (or where a manual said he would be). Through Reading Recovery I found ways to help this child learn in all areas throughout his school day. I had the freedom to create learning opportunities based on what the student found interesting and motivating. It appears likely that this child will become a student who receives special education services. The information that I learned about this student and how he learns will be important and helpful information to add to his I.E.P.

As a teacher, this student helped me to:

- become a more skillful observer

- be even more intentional in my planning

- be more explicit in showing what is known embedded in text

- not underestimate the power of using student’s interests

How did your first round go this school year? What have you learned from your hardest to teach students?