Running Records are an essential component of my day-to-day planning for my students. At times, I hear running records talked about in terms of a student “passing” or “failing”. When we put too much emphasis on the accuracy rate and think of running records as “pass/fail,” we can not make student-centered decisions about our teaching.

A running record is a formative assessment that can give the teacher detailed information about what strategic actions a child uses while reading. The teacher is also able to see how effective his/her teaching was from the previous day. For example, if I demonstrated for a student how to start words using larger word parts rather than simply using the first letter, I would want to see evidence on the running record that they are taking on this learning. Running records inform our teaching in real-time, so we are able to provide the student with the learning they need right there in that same lesson.

The accuracy rate does not tell you how a child processed the text. The accuracy rate is simply a guideline to use when thinking about how difficult the book was for the child. The self-correction rate provides us with information regarding how well our student is monitoring his/her reading. The analysis of the running record is the piece that will best inform our teaching.

I would like to share some running records with you to further demonstrate the importance of analyzing a student’s errors rather than solely relying on the accuracy rate. I left my analysis off of the running record form and would like to invite you to analyze the running records before reading my own analysis beneath each running record. As you analyze each running record, think about the following questions.

- What behaviors are you noticing?

- Is the student self-monitoring?

- Does the child initiate problem-solving?

- What sources of information does the child use or neglect?

- Where could we go next with this student?

Running Record #1 Accuracy Rate: 90%, Self-Correction Rate: 1:3

This student had 4 repeated errors where he substituted the word “sleeping” for “asleep”. We had been working on checking the first letter and we can see that reflected in the way he start, “t-t-time”, his self-correction of “said” for “woof”, and when he overtly checks to see if the word is “woof” as he says what he sees, “t-t-t”. I did praise the child for all of the checking and problem-solving they did. I also showed the child that another way to say “Dad is sleeping” is “Dad is asleep” to help build their oral language.

Running Record #2 Accuracy Rate: 76%, Self-Correction Rate: 1:13

If we only look at the accuracy rate, we might assume that this book was too difficult for the student. This running record is a good example of oral language override. His oral language game is so strong that the visual mismatch was missed as he read “said” for “went” during much of the story. Toward the end of the story, he caught his error, fixed it, and on the next page he slowed down and accurately read the page. I was able to bring him back to the place where he made sure it sounded right and looked right to reinforce that behavior.

Running Record #3 Accuracy Rate: 89%, Self-Correction Rate: 1:4

The accuracy rate can be misleading with level A and B texts if we are not looking closely at behaviors. Sometimes, students are kept in these levels for far too long because they may have lower accuracy rates. When I analyzed this running record, I saw a student who was ready to take on level B texts despite this accuracy rate being in the hard range. What you can’t see from this one running record is that this student had multiple consecutive running records that displayed similar behaviors as seen on this running record. The child consistently used one-to-one matching, knew where to start reading, and read left to right. The student knew that reading had to be meaningful and used the pictures to support meaning. The student also showed evidence of self-monitoring when he read “my” accurately after substituting “Danny’s” on the 2 pages. He also noticed the visual mismatch when he read “bee” for “toy” and then when on to fix it. I reinforced the behavior of noticing when something doesn’t look right. We also worked on making “my” more well-known, found it several times in this book and other books he has read, and then reread several pages of the running record book.

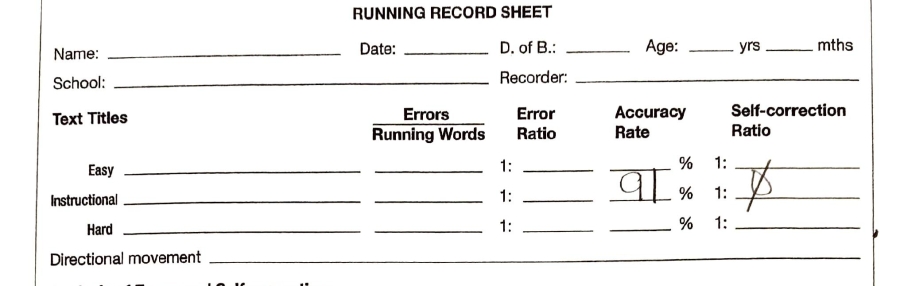

Running Record #4 Accuracy Rate: 91%, Self-Correction Rate: 1:0

Running records like this set off red flags for me. The student’s strategies for problem-solving were to appeal and take his eyes off the text. These are not very helpful problem-solving behaviors. The student did not notice the gross visual discrepancy between “clown” and “balloon”, but I was glad that the student at least attempted something meaningful. I showed the child how he could use the first letter to start the word while he thought about the story.

As I mentioned earlier it is helpful to make time to look at a few consecutive running records in order to see patterns over time. Are there patterns of appeals, tolds, eyes off text, or any other unhelpful behaviors? Is the child showing evidence of taking on the behaviors you have taught and prompted for?

When you were looking at my running records you may have noticed patterns or behaviors that I didn’t notice. You might have thought about taking the child in a different direction with his/her learning. This speaks to the importance of looking over running records with other teachers. This is especially important for any student who has plateaued in progress or who is making slow progress.

To help shift the talk about running records, I would like to propose a challenge. At our future meetings with parents, teachers, and administrators let’s ground our talk in student behaviors and not numbers like accuracy rates.

If you would like to read more about running records, the following are links to previous posts: